Black-owned businesses in Weeksville, an independent Black village in Crown Heights

This year, Black History Month was a chance to reflect on the amazing legacy of Black organizing for community control of land and housing in New York City.

The story of HDFC co-ops in New York City is one of community resistance to housing discrimination. We’ve explored how communities of color used HDFC co-ops as a way to take control their housing in the face of racist redlining policies; however, this is only one piece of the history of struggle for community control in New York City.

Here are three examples from New York City’s rich history of Black organizing for community control of land and housing. You can also explore these histories on UHAB’s instagram.

Weeksville

Weeksville was an independent Black village in current-day Crown Heights where Black New Yorkers took refuge from the racist violence of the nearby city.

At the time of the revolutionary war, most of Central Brooklyn belonged to the Lefferts family, who were among Brooklyn’s largest landowners and slaveholders. Shortly after slavery was abolished in New York in 1827, abolitionist leader Henry C. Thompson purchased land from the Lefferts and sold it to James Weeks, who began a community named Weeksville.

Weeksville had over 500 residents during the mid-1850s, and became home to a small but growing Black middle class. It became home to Black-owned businesses, churches, and schools. Black Manhattanites took refuge in Weeksville during the Draft Riots of 1863.

By the 1880s, the street grid began to catch up to and expand through Weeksville. By the 1930s, it had been almost entirely absorbed by Brooklyn. Today, the site is home to the Weeksville Heritage Center.

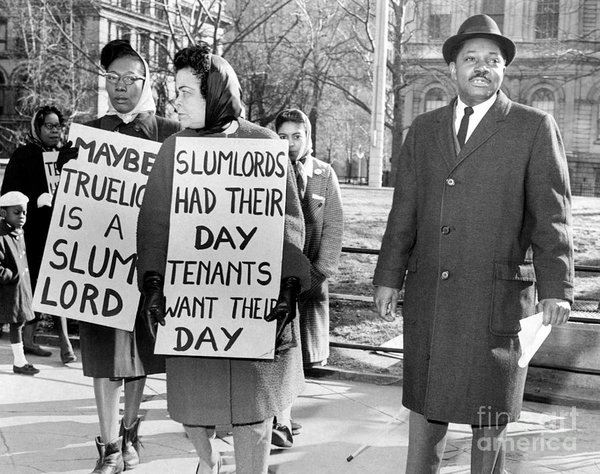

Jesse Gray and New York City’s Largest Rent Strike

In 1960s Harlem, Black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers paid more than white New Yorkers for their apartments, but experienced far worse living conditions. Tenants in disinvested neighborhoods like Harlem faced months without heat, a lack of security, and rodent infestations. 1962 alone, the City Bureau of Sanitary Inspections reported 530 children bitten by rats in their homes.

Jesse Gray was born in Baton Rouge, Mississippi. He joined the Harlem Tenants Council in 1952, when his heat went out. He explained his motivation for organizing simply: “I was cold.”

In 1963, Jesse Gray led one of the most infamous rent strikes in Harlem history. After a month on strike, thirteen families brought dead and living rats into housing court to demonstrate the living conditions they were subjected to. By 1964, the strike had spread from Harlem to the Bronx and the Lower East Side. It remains the largest rent strike in New York City history. Tenants won a $1 million rat extermination bill and repairs on dozens of buildings.

Seneca Village

Seneca Village was established in NYC in 1825. The village was ultimately destroyed to make way for Central Park. Free Black New Yorkers moved to Seneca village to escape racial violence and poor living conditions. The first residents of Seneca Village moved there in 1825, two years before slavery was abolished in New York. Over half the population owned their own homes, and the community developed churches, a cemetery, and schools.

In 1853, the city seized the land via eminent domain to build Central Park, displacing Seneca Village and several other settlements in the area. Seneca Village’s residents resisted displacement for two years through protest and petition, but city officials ultimately seized their homes.

Seneca Village’s destruction created a precedent where Black and Brown communities were razed to make way for amenities that, because of physical displacement and heavy policing, they could not enjoy.